As text-to-IMAGE AI excites and enrages the world, the 105 artists calmly ponder the joys of using AI to make art.

Text-to-image AI has hit the collective imagination big time since companies like Midjourney and DALL-E opened to the public last year. Servers are grinding away with the storm of activity, and social media feeds are clogged with images claiming to interpret our thoughts via words.

The buzz is equal only to the angry denunciation: this usually happens when a critical mass of people suddenly get access to a paradigm-shifting tool. People from all walks of life — musicians, sculptors, data scientists, teachers, truck drivers! — are at it. And why shouldn’t they be? Everyone needs an outlet for creative expression. Meanwhile, established traditional artists are (somewhat understandably) outraged that their styles have been scraped unceremoniously and nonconsensually into the communal electric brain.

As experimental digital artists, we’re here to add to the conversation, not point fingers. Besides, four out of five of us have, to some degree, already been using AI tools in our work for a number of years. We’re an inquisitive bunch, so of course we’re gonna tinker with the new toy. We thought that instead of joining the debate, we’d take this opportunity to show you some of our AI-infused artworks, past and present. Enjoy!

// OCULARDELUSION

Past: Deep Dream, ArtBreeder

Latest: Playform, Midjourney

Do Androids Dream of Electric Kool-Aid? (2022) by oculardelusion. A self-portrait as a bridge between the physical, human consciousness, and the digital realm, and interrogating my willingness to be subsumed. Photography, Deep Dream, and digital illustration and animation.

I first became aware of AI being used to create poetry around a decade ago, and first witnessed neural style transfer — taking the style from one image and applying it to another — about four years ago. The idea of making art in conversation with computers not only doesn’t scare me, but one of my thematic preoccupations is the effect of technology on human consciousness. I’m usually happiest splashing around in the limbo between digital and physical, and my practice usually involves mashing up artmaking technologies to open portals into new realities.

In early 2020, I began experimenting with style transfer apps like Deep Dream and ArtBreeder in combination with 2D digital painting and animation, photography, and VR art. I found the style transfer process satisfying on many levels: it introduced a sense of the irrational, added an element of chance, and exploded depth, texture, and color possibilities.

“There is no noise like the rare silence” (2022) by oculardelusion. This began life as a doodle on Playform, and I took it through more than 50 translations before choosing one and completing it using digital illustration. I often find titles by opening nearby poetry books. The phrase where my finger lands at random becomes the title — a bit like using the I Ching, or indeed like dialogue with an AI. In this case, it’s from Frank O’Hara’s “Poem Read at Joan Mitchell’s”.

I also enjoy the layering of realities. I’m distorting my own vision — already the product of environment, education, and intergenerational and collective consciousness — through the collective intelligence of all those humans who came to play before me. Then the output can be once again curated and refined by me, and I can go around and around as long as I want. I think of it as sort of a large-scale glitch process.

Then came the Midjourney beta. I thought that as a writer, it would be easy. I entered various prompts in Discord and churned through the process. Here are some examples.

“No one, not even the rain, has such small hands” (2022) by oculardelusion. As a lapsed poet, the first thing I wanted to do when faced with text-to-image technology was see how the computer would convey lines from favorite poems. The result (a literal rendering of an exquisite metaphor) was disturbing, compelling, and hilarious. The Midjourney AI is slowly getting better at hands, by the way, which is a shame.

Batty (2022) by oculardelusion. I prompted Midjourney with familiar totems and themes to see whether it would make art that resembled my own. The result was more horrifiying than anything I could have ever come up with myself, which I quite enjoy.

The examples I’ve given above are my favourites so far, but typically, the image bank Midjourney draws from is not at all what I want, aesthetically. Yes, I could amend my prompts, but then it becomes a drawn-out exercise in learning how to manipulate the machine to get an image. This is less fun than other processes I use. Meanwhile, I’m aware I’m wasting a lot of processing power and energy.

I do see art made using TTI that I enjoy, that even moves me. I often hear TTI artists defend what they are doing. I don’t think it’s necessary to apologize. To one traditional artist friend who has managed to create stunning artworks but feels weird about it, I said, “Maybe collective artmaking is ok. Maybe individual artmaking was always an illusion. But I CAN say that these would not have happened without you, any more than your paintings could happen without you — or your brush and palette makers and paint manufacturers and the history of art behind you.”

// UNREALCITY

Past: Artbreeder/ Ganbreeder, Google Deep Dream

Latest: Google Text 2 Dream

“Arm One Woman And Leave” (2021) by UnrealCity

Like Karen, I first encountered AI in the arts sphere through poetry. A couple of years ago, I introduced a lecture on poetry generated by AI, during which the speaker gave out some verse — some by machine poets, some by meat poets — and challenged the delegates to assess them and file them appropriately (if anonymously, so as to save us professional embarrassment) in two labelled boxes at the front of the hall.

76% of the poems were filed correctly.

It was a surprisingly easy exercise: while individual lines and figures of speech did not diverge significantly between the machine poems and meat poems, the latter had a greater conceptual unity, or at least a sense of an accretion of technique towards a single end: the rhythm spoke to the lexis, the lexis spoke to the figurative language, the parts spoke to the whole.

And that speaks to me: I regard AI as a tool for, or even an assistant to, the intentionality of the human artist.

In my own practice, what I want AI to do is the things I can’t do, or at least the things I can’t do easily, either because I don’t have the skill or because I don’t have the time. I recognise many artists are a lot more exploratory and less intentional than I am and that’s perfectly valid, of course: I understand the excitement of discovering what emerges from an equal conversation between meat and machine. But personally, I have a pretty complete notion of what I want to make in my head before I start making it, and although that will obviously evolve (as the spirit of Bob Ross sprinkles the fairy dust of happy little accidents over the canvas, screen or pile of disparate rubbish I’m screwing together as a sculpture), I always feel I’m making deliberate decisions to serve an overarching end. AI to me is about looking for artistic solutions by design, not finding them by accident.

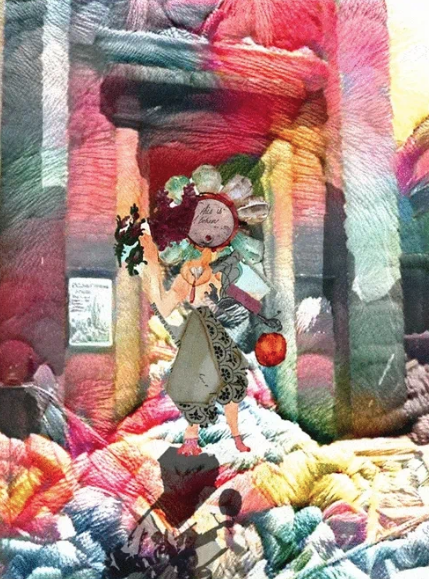

“This Is A Token” (2021) by UnrealCity

For example, “This Is A Token” is a digital collage based on a GAN AI figure originally constructed on Artbreeder as a skeleton or sketch, and then composed of tokens left with Foundling Hospital children by their parents to identify them. I placed this on a background generated from an original photograph and mapped to skeins of wool using Google Deep Dream. That hybrid method allowed me to make the familiar strange, locating the piece as a representation of reality from a certain perspective or emotional state — the Unreal City I so often come back to — rather than as an image from either a fantasy world or from our shared orthodoxy of the real.

The work looks something like the notion I had in mind when I was first organizing my thoughts, that intentionality underpins it, whilst preserving that sense of the other and strange I want to participate in as the artist rather than to just manufacture for the viewer. I arrived at “Now There’s A Tragic Waste Of Brutal Youth” with similar tools and methods, letting the decisions about the AI enhancement distance the photographic image from me as much as for anyone else.

“Now There’s A Tragic Waste Of Brutal Youth” (2021) by UnrealCity

In “Arm One Woman And Leave” I wanted the method to reflect evolution, with a range of iterations created by AI as the random variation and my artistic internationality as the deterministic selection. The title came by asking visitors to my house to use magnetic poetry to compose lines on the meatspace mannequin sculpture, as she’s painted with an iron-based rust patina system used by car modifiers, and then I chose between their compositions to look for meaning and an organizing principle for my visual selections for the final representation of the sculpture. The piece feels like a collaboration between intent and the random, more than anything else I’ve done, and the speed of iteration when using AI made that approach practical. Again, the AI is a tool or an assistant to my intentionality as an artist, only with this piece I let that intention itself generate through a conversation with intelligences other than my own, both human and artificial.

It’s often been pointed out that no new technology has ever truly usurped an old one: the motor car never completely replaced the horse, the rifle never completely replaced the bow, the microwave never completely replaced the campfire. Obsolescence is contextual. The trick is, I think (to get back to the poetry) to “commit the oldest kinds of sins in the newest kinds of ways”.

// STINA JONES

Past: Playform

Latest: DALL•E 2

Hand-drawn input vs GAN output. GANOODLES experiments (2020) by Stina Jones.

I first discovered AI art in 2019 while browsing KnownOrigin. As an artist, I was intrigued by the concept of generative adversarial networks (GANs) and wondered if I could use them to create variations of my own hand-drawn works. I decided to give it a try and see what would happen.

I already had a folder full of character doodles on my iPad, all with similar proportions and colour palettes, so I uploaded them to Playform.io and used their online service to train a GAN model on the dataset. The results were pretty unexpected: while my original characters were made of simple geometric shapes, the generated images were much more abstract and free-flowing. I was drawn to the glitches and random shapes, so I decided to take my favourite results and repaint them using Procreate, creating a series of artworks that I called GANOODLES. This process of hybridising GANs with my own doodle art was exciting and opened up new possibilities to explore.

First completed GANOODLE artwork (2020) by Stina Jones.

More recently, I have been experimenting with DALL·E 2, a text-to-image AI tool that uses machine learning techniques on a more comprehensive dataset. Instead of being influenced by a specific set of images, DALL·E 2 looks for patterns on text-image pairs from a variety of sources.

Text-to-image experiments with DALL·E 2 (2022) by Stina Jones.

The outputs are certainly impressive, but lack the lo-fi charm that made my GANOODLES series so interesting to work on. DALL·E 2 seems more useful for its practical applications such as generating textures, collage elements, or reference images.

However, these use cases also present their own set of limitations. As I was using it to generate different facial expressions for reference in my sketchbook work, I noticed representational biases reflected in underspecified results. The developers of DALL.E 2 have acknowledged this issue and are working on ways to mitigate it. Still, it raises concerns about the potential for this technology to create harmful feedback loops.

Overall, my experiments with AI art have been interesting and thought-provoking. It’s fascinating to see how these tools can be used to generate images, but it’s also important to consider their limitations and potential impacts. I’m still figuring out if and how image synthesis will fit into my own workflow, but I don’t see it as a substitute for commissioning artists. Artists bring vision and a unique perspective to creating compelling works, whatever tools they choose to use.

// THE 105 COLLECTIVE

We’ll end with this: when the 105 first started chatting about our individual experiments with TTI, Stina had an idea: what if we combined a bunch of random text prompts from everyone in the group to see what would happen? After all, we’d already been working on an Exquisite Corpse project (the Surrealists’ game of adding to a previous artists’ partly concealed piece). This seemed like an extension of that exercise. Here are some of the results.

The results of one of the 105 collective experiments with text-to-image AI. What does this say about us as a group? Prompts, from top: “A nocturnal owl sits inside a glowing mechanical vehicle, its dark metallic eyes fixed on the dramatic nebula above”; “A small neon carrot with a determined expression, illuminated by a natural sidelight”; “A surreal scene with a group of random astringent carrots dance and spin in a world made of flying geometric shapes, their iridescent forms reflecting the light of the glowing midnight sky above.” Participants: urben, Stina, Unrealcity, oculardelusion